Socialism offers diverse, often misunderstood frameworks for economic democracy. Its principles—worker control, distributed ownership, anti-managerialism—inform today’s experiments in cooperative governance, decentralized systems, and humane, post-capitalist organizational design.

This article was written by Claude based on a deep research report from Gemini and then lightly edited by the administrator. Inaccuracies may exist.

Socialism: What It Really Means and Why It Matters for Modern Organizations

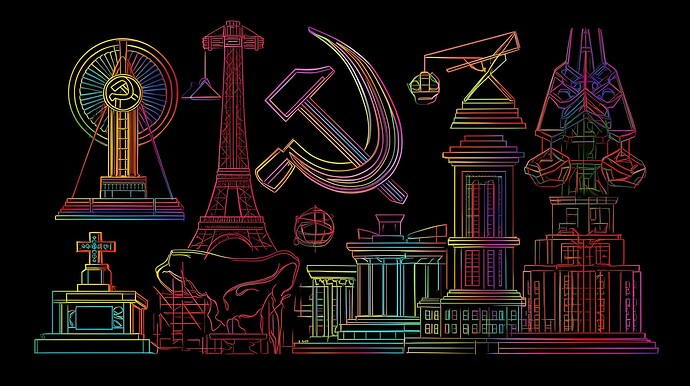

Socialism might be one of the most misunderstood concepts in modern political discourse. To some, it conjures images of Soviet breadlines and authoritarian regimes. To others, it represents an idealistic vision of economic equality and worker empowerment. The reality is far more nuanced and, frankly, more interesting than either caricature suggests.

Rather than being a monolithic ideology, socialism encompasses a diverse family of ideas united by a few core concerns: the exploitation of workers under capitalism, the concentration of economic power in private hands, and the belief that society’s productive resources should serve collective rather than purely individual interests. Understanding this diversity isn’t just an academic exercise—it offers valuable insights for anyone grappling with questions about organizational structure, worker autonomy, and economic democracy in the 21st century.

The Many Faces of Socialism

The term “socialism” was reportedly coined in French in 1834 as a deliberate contrast to “individualism”—a concept early socialists saw as symptomatic of moral decay and unbridled pursuit of wealth. From the beginning, socialism carried both an economic and ethical dimension, proposing not just different ownership structures but an entirely different moral framework for society.

The socialist family tree includes several major branches, each with distinct approaches to achieving their shared goals:

Democratic Socialism advocates for democratically elected governments managing key industries while maintaining markets for consumer goods. Think of essential services like energy and healthcare run through public planning, while everyday products remain available through market mechanisms. Unlike social democracy (which aims to regulate capitalism), democratic socialism seeks to transform the economy from capitalism to socialism through democratic means.

Revolutionary Socialism takes a harder line, arguing that capitalism cannot be reformed but must be overthrown. In this view, peaceful coexistence between capitalist and socialist systems is impossible—fundamental change requires revolutionary struggle, with workers taking control of production through centralized structures.

Libertarian Socialism operates from the optimistic assumption that people are naturally rational and self-determining. Remove capitalism, the theory goes, and people will naturally gravitate toward cooperative, non-hierarchical arrangements that better serve everyone’s needs.

Market Socialism attempts to have it both ways: social ownership of productive assets combined with market mechanisms for allocation. Workers control production and decide how to distribute resources, but markets still play a role in coordination and pricing.

Anarcho-Syndicalism goes further in rejecting centralized power, advocating for worker control through democratically run unions without any state apparatus. The goal is ending “wage slavery”—the situation where economic pressure forces workers to accept poor conditions and low pay.

Marxism-Leninism, the ideology that dominated much of 20th-century socialism, emphasizes a “vanguard party” of class-conscious intellectuals leading a one-party state toward eventual communism.

This diversity reflects fundamental disagreements about power, efficiency, and human nature. Some variants trust centralized state power as a tool for transformation; others view any concentration of authority with deep suspicion. Some see markets as inherently exploitative; others believe they can be harnessed for social good. These aren’t merely theoretical differences—they’ve played out in dramatically different ways throughout history.

The Historical Context: Why Socialism Emerged

Socialism didn’t arise in a vacuum. It emerged from the collision of two revolutionary forces: the ideological upheaval of the French Revolution and the economic transformation of the Industrial Revolution.

The French Revolution had shattered traditional notions of social order, demonstrating that long-established hierarchies could be dismantled and that radical change was possible. Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution was creating unprecedented wealth alongside unprecedented misery. Early socialists were horrified by the conditions they witnessed: exhausting work for minimal pay, dangerous factories, child labor, and sprawling urban poverty.

Early socialist thinkers like Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, and Charles Fourier—later dubbed “utopian socialists”—believed that rational people, including the wealthy, would eventually recognize the benefits of reorganizing society along more cooperative lines. Saint-Simon envisioned an industrial society guided by scientific principles. Owen, a factory owner himself, implemented reforms at his New Lanark mills and established experimental communities. Fourier designed elaborate theories about organizing society into “Phalanxes” where work would align with individual passions.

These early socialists were fundamentally optimistic about human nature and the possibility of peaceful transformation through moral persuasion. They focused on restoring “organic social bonds” they felt were being dissolved by competitive individualism.

This optimism didn’t survive the failed revolutions of 1848. When it became clear that both conservative and liberal elites viewed socialism as a threat worth suppressing violently, socialist thought became more militant. The idea of class collaboration gave way to an emphasis on class struggle as the engine of historical change.

This shift set the stage for Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who sought to move socialism from “utopian” aspiration to “scientific” analysis. They developed comprehensive theories about capitalism’s internal contradictions, the historical role of the working class, and the inevitable transition to socialism—not through moral conversion, but through revolutionary struggle.

The Socialist Critique of Work Under Capitalism

Central to socialist thought is a fundamental critique of how work is organized under capitalism. This critique goes far beyond complaints about low wages to encompass what Marx called “alienation”—a condition where work becomes a source of estrangement rather than fulfillment.

Marx identified four interconnected forms of alienation. First, workers are alienated from the products of their labor. They create goods they don’t own or control, which then confront them as alien objects in the marketplace. Second, workers are alienated from the act of production itself. Work becomes “forced labor”—something done purely for survival rather than creative expression or personal development.

Third, workers are alienated from their “species-being”—their essential human nature as creative, conscious beings. Capitalism reduces labor to monotonous, coerced tasks that prevent people from realizing their fundamental human potential. Finally, workers are alienated from each other, as competition and commodification replace genuine human relationships.

Alongside alienation, socialists emphasize exploitation through what Marx called “surplus value.” The basic idea is straightforward: workers are paid less than the full value their labor creates. If a worker can produce enough to cover their own subsistence in five hours but works for twelve, the capitalist appropriates seven hours’ worth of value as profit. This extraction is possible because workers, lacking ownership of productive assets, must sell their labor power to survive.

The Labor Theory of Value provided the analytical framework for this critique. While mainstream economics has largely moved away from this theory, it served as a powerful tool for arguing that capitalist profit wasn’t primarily a reward for risk or innovation, but an extraction from workers’ labor.

Socialist alternatives to capitalist labor organization have varied widely. Some emphasized state control over industries and central planning. Others advocated for worker cooperatives where employees collectively own and control their enterprises. Anarcho-syndicalist models proposed democratic unions as the basis for economic organization, with minimal hierarchy and maximum worker participation.

A crucial distinction in socialist thought is between “personal property” (items for individual consumption like homes, clothing, and personal tools) and “private property” (means of production used to generate profit through others’ labor). Socialists typically support personal property rights while advocating for social ownership of productive assets.

Socialism in Practice: Lessons from History

The 20th century provided numerous opportunities to test socialist ideas in practice, with results that were mixed at best and catastrophic at worst.

The Soviet Experiment

The Soviet Union represents the most ambitious attempt at centrally planned socialism. Initially, the system achieved impressive results, transforming a largely agricultural society into a major industrial power. Between 1928 and 1940, the USSR’s Gross National Product grew at an estimated 5.8% annually.

However, by the 1970s, the system had entered prolonged stagnation. Having caught up with Western industrial capacity in basic sectors, the Soviet system struggled with innovation, particularly in civilian industries. Much of the country’s research and development resources were diverted to military purposes during the Cold War.

The fundamental problem was the absence of market-generated price signals. Without accurate information about consumer demand, resource costs, and production efficiency, central planners made increasingly poor decisions. This led to chronic shortages of desired goods, wasteful surpluses of others, and a general inability to respond to changing conditions.

Reform attempts in the 1980s—Perestroika and Glasnost—inadvertently destabilized the existing system without creating a viable alternative. The concentration of both economic and political power in the hands of the state and party proved unsustainable.

Yugoslavia’s Third Way

Yugoslavia attempted a unique path: market socialism with worker self-management. Beginning in 1950, the country mandated workers’ councils in enterprises, theoretically empowering employees to manage their own affairs, influence production decisions, and share in surplus revenue.

The system achieved periods of significant development and was credited with fostering some degree of ethnic cohesion. Self-managed enterprises often became centers of decentralized welfare, providing housing, healthcare, and even vacations for workers.

However, despite formal structures of worker control, enterprise directors and technical managers often retained real decision-making power. The introduction of market mechanisms, while improving efficiency, also brought familiar capitalist problems: social differentiation, unemployment, and regional inequalities. These issues contributed to the rise of nationalist ideologies that ultimately tore the country apart.

The Mondragon Success Story

The Mondragon Corporation in Spain’s Basque Country offers a more successful example of cooperative socialism. Founded in 1959, it’s now a large federation of worker cooperatives operating on principles of cooperation, participation, social responsibility, and innovation.

Worker-owners collectively own the business and participate in its financial success based on their labor contribution. Governance follows “one worker, one vote” principles, with compressed wage ratios between executives and workers (typically 3:1 to 9:1, averaging around 5:1).

Mondragon has demonstrated remarkable resilience, particularly during economic crises. Inter-cooperative solidarity and mutual support mechanisms help struggling cooperatives through capital transfers, worker retraining, and relocation programs. Their social welfare cooperative, Lagun Aro, provides unemployment benefits, pensions, health coverage, and retraining funding.

Key to Mondragon’s success appears to be not just formal structures but a deep-rooted culture of solidarity, emphasis on education and continuous learning, and robust mechanisms for mutual support.

The Nordic Model: Capitalism with a Human Face

The Nordic countries are often cited in socialist discussions, but their system is more accurately described as social democracy within a market capitalist framework. While socialist parties played important historical roles, these countries maintain strong private property rights and market-based economies.

What makes the Nordic model distinctive is comprehensive welfare states, universal public services, and robust collective bargaining between employers’ organizations, trade unions, and government. High taxation supports extensive social safety nets designed to reduce inequality and provide economic security.

The model demonstrates that high levels of social equality and worker protection are possible within capitalism, but its success depends on specific conditions: strong, centralized unions, cooperative employers, high social trust, and political consensus supporting high taxation for collective benefit.

What Socialism Offers Modern Organizations

While grand 20th-century socialist projects have largely receded, their core insights remain surprisingly relevant for contemporary organizational design, particularly for companies exploring flatter structures, worker empowerment, and distributed control.

Beyond Hierarchy and Managerialism

Socialist traditions, especially anarchism and libertarian socialism, offer fundamental critiques of hierarchy that resonate with modern organizational frustrations. They view concentrated authority not just as inefficient but as a primary source of oppression and alienation.

“Managerialism”—the ideology that legitimizes professional managers as uniquely qualified to run organizations—maintains power dynamics and prevents genuine economic democracy. This critique anticipates modern concerns about agency problems, where managers pursue their own interests rather than those of shareholders or other stakeholders.

The contemporary push for self-managing teams, holacracy, and other flat structures isn’t just about efficiency—it’s about fulfilling fundamental human needs for agency and purpose, themes central to socialist thought.

Cooperative Models as Organizational Blueprints

Worker cooperatives and self-management systems offer practical lessons for modern decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) and managerless structures:

Governance Models: The “one worker, one vote” principle and democratic decision-making processes provide established precedents for DAO governance structures that distribute voting power among contributors rather than concentrating it in the hands of passive investors.

Incentive Alignment: Worker ownership naturally aligns individual incentives with organizational success. DAOs use similar mechanisms through tokenization, staking, and innovative voting systems to reward participation and align interests.

Shared Purpose: Organizations like Mondragon succeed partly through strong shared values and missions extending beyond profit maximization. DAOs also frequently coalesce around clearly defined purposes, whether building technology, managing digital commons, or pursuing social causes.

Resilience and Mutual Support: Mondragon’s inter-cooperative support mechanisms—capital transfers, worker reallocation, comprehensive social services—could inspire mutual insurance schemes or solidarity funds within DAO ecosystems.

Distributed Control and Decentralized Planning

While Soviet-style central planning failed spectacularly, some socialist theories have long advocated for more decentralized approaches. Modern distributed control systems in industry demonstrate that technology can significantly aid in coordinating complex operations without hierarchical control.

The socialist principle of “social ownership by those affected” offers a powerful guide for designing governance in distributed networks. Control rights should accrue to active participants and direct stakeholders rather than passive owners or unaccountable authorities.

Socialist emphasis on production for “use-value” (meeting real needs) rather than “exchange-value” (maximizing profit) could guide DAOs and platform cooperatives toward creating genuine utility rather than pursuing speculative gains.

Learning from Anarchist Self-Organization

Anarchist thought provides particularly relevant insights for truly autonomous teams. Core principles include:

Self-Organization: Anarchist Colin Ward argued that “given a common need, a collection of people will, by trial and error, by improvisation and experiment, evolve order out of chaos.” This challenges assumptions that order must be designed and imposed from above.

Direct Action: Encouraging proactive problem-solving and initiative rather than waiting for permission from higher authorities.

Solidarity and Mutual Aid: Fostering strong bonds and practices of mutual support enhance collaboration, knowledge sharing, and collective problem-solving.

Vigilance Against New Hierarchies: The comprehensive anarchist critique of all coercive hierarchy warns that genuinely decentralized organizations must actively prevent informal power dynamics from creating new forms of domination.

Navigating the Challenges

Translating socialist principles into modern organizational practice requires addressing the same fundamental challenges that historical socialist experiments grappled with: incentives, coordination, and scalability.

The Incentive Problem

Many socialist systems struggled to design effective incentive structures when moving away from direct monetary rewards tied to individual performance. The principle of “to each according to his contribution” sounds fair but measuring contribution equitably in complex settings proves difficult.

Modern DAOs experiment with tokenization, staking, and quadratic voting, but face similar challenges: How do you reward valuable contributions that are hard to quantify? How do you prevent purely speculative behavior? How do you avoid creating new forms of inequality or exclusion?

Coordination Complexity

Large-scale central planning failed due to information overload and slow adaptation. While modern distributed control systems show that technology can aid coordination, decentralized organizations still face the challenge of achieving coherent action across many autonomous units without resorting to hierarchical control.

This requires robust communication protocols, shared understanding of goals, effective conflict resolution, and ways to avoid both fragmentation and the “tyranny of structurelessness” where unclear processes lead to informal power grabs.

Scaling Democratic Participation

Many successful small-scale cooperatives and communes have struggled to scale up while maintaining their founding principles. Mondragon is a notable exception, but its success depends on specific cultural and historical contexts that may not be easily replicated.

DAOs face similar challenges: technical limitations in blockchain throughput, difficulties achieving broad participation in governance as membership grows, and risks of core principles diluting with expansion.

The key lesson from historical socialist failures is that formal rules and structures are insufficient. Robust, transparent, and culturally embedded mechanisms are necessary to prevent re-concentration of power and ensure genuine democratic participation.

Personal Property vs. Private Property: A Distinction That Matters

One of the most persistent misconceptions about socialism is that it involves confiscating all personal possessions. This confusion stems from failing to distinguish between personal and private property—a distinction that’s increasingly relevant for modern organizational design.

Personal property encompasses items for individual consumption: homes people live in, personal vehicles, clothing, tools for hobbies. Socialists generally affirm these rights and argue that equitable wealth distribution would enable more people to possess adequate personal property.

Private property, in the socialist critique, refers specifically to productive assets used to generate profit through others’ labor: factories, large-scale farms, rental properties. The target of socialist transformation isn’t personal belongings but ownership structures that enable systematic exploitation and concentration of economic power.

This distinction helps clarify what’s at stake in discussions about alternative organizational models. The question isn’t whether individuals can own things they use, but whether productive assets should be controlled by those who contribute labor versus those who contribute only capital.

Looking Forward: What We Can Learn

Socialism’s diverse intellectual tradition offers valuable insights for anyone interested in more democratic, equitable, and humane forms of organization. The failures of 20th-century state socialism shouldn’t overshadow the enduring relevance of its core questions: How should work be organized? Who should control productive resources? What’s the purpose of economic activity?

For modern organizations exploring flatter structures, worker empowerment, and distributed control, socialist thought provides both inspiration and cautionary tales. The emphasis on education, consciousness-raising, and member development—evident in successful cooperatives like Mondragon—remains crucial for any organization seeking genuine participation rather than mere formal democracy.

The anarchist insight that “given a common need, a collection of people will evolve order out of chaos” offers a powerful alternative to management paradigms that assume order must be imposed from above. But the Yugoslav experience reminds us that formal democratic structures can be captured by new elites if not supported by robust cultural and procedural safeguards.

Perhaps most importantly, socialism’s persistent focus on human dignity, collective welfare, and the belief that economic systems should serve people rather than the other way around provides a moral compass for organizational design. In an era of increasing inequality, climate crisis, and technological disruption, these concerns remain as urgent as ever.

The future of work may not look like 20th-century socialism, but it could benefit from socialism’s enduring insights about cooperation, democracy, and the potential for humans to organize themselves more justly and sustainably. The question isn’t whether to adopt any particular socialist model wholesale, but how to learn from this rich tradition while creating new forms of organization appropriate for contemporary challenges.

Sources

- Socialism Wikipedia Entry

- The Policy Circle - Socialism: Understanding Its Core Principles

- Wikipedia - Socialism

- Lumen Learning - The Disadvantages of Socialism

- Corporate Finance Institute - Socialism

- Wikipedia - Democratic Socialism

- Wikipedia - Types of Socialism

- Number Analytics - Comparative Analysis of Socialist Systems

- Vaia - Anarcho-Syndicalism

- IWW - Introducing Anarcho-Syndicalism

- Wikipedia - Marxism-Leninism

- Lumen Learning - Life in the USSR

- Wikipedia - Anarchism

- Humanities LibreTexts - Socialism

- Wikipedia - Henri de Saint-Simon

- Britannica - Henri de Saint-Simon

- Wikipedia - Robert Owen

- EBSCO Research Starters - Analysis: Manifesto of Robert Owen

- SocialistWorker.org - Ten Socialist Classics

- Econlib - Marxism

- Wikipedia - History of Socialism

- JGU - Karl Marx’s Theory of Alienation

- Study Rocket - Alienation & Exploitation

- Wikipedia - Socialist Mode of Production

- Philosophy Stack Exchange - Marxist Critique of Capitalism

- Wikipedia - Labor Theory of Value

- Wikipedia - Labor Theory of Value (Classical Economics)

- Wikipedia - To Each According to His Contribution

- Brian Martin - State Socialism

- Investopedia - Soviet Economic System

- Wikipedia - Council of Labor and Defense

- Wikipedia - Socialist Self-Management

- CIA - Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Self-Management

- Wikipedia - Socialist Self-Management

- Reddit - Socialist Society Employment Management

- ResearchGate - Yugoslav Self-Management

- Reddit - Property Rights Under Socialism

- Investopedia - Soviet Economic System Consumer Goods

- Investopedia - Why the USSR Collapsed Economically

- University of Utah - The Rise and Decline of the Soviet Economy

- ResearchGate - Workers’ Councils in Yugoslavia

- Wikipedia - Mondragon Corporation

- Oxford Saïd Business School - Mondragon Case Study

- Round Sky Solutions - Visiting Mondragon

- Democracy at Work Institute - What is a Worker Cooperative?

- Wikipedia - Nordic Model

- European Parliament - Social and Labour Market Policy in Sweden

- European Parliament - Labour Market Legislation

- L&E Global - Labour & Employment Law Sweden

- Economics Help - Pros and Cons of Socialism